As the global population increases, we are seeing a sharp increase in the worldwide demand for minerals and metals. The mining industry is responding to this call in a big way through automation, smart sensors and the use of artificial intelligence. These technologies are helping mining companies across the globe to increase efficiencies in the face of declining ore grades as they look to convert mineral resources into reserves and, in turn, increase the availability of mineral resources to deliver on the value proposition of their businesses.

Escalated demand and increased technological deployment bring about their own set of unique challenges for the future of mining but possibly the most daunting disruption is the myriad of social challenges now confronting the sector. Expectations around long-term sustainability of resource rich communities is a leading concern for mine owners as they balance the scales of people, planet and profit. The calls are not new, but they are certainly louder, as mining-community conflict appears to be increasing and these conflicts are proving costly for companies and communities. Davis and Franks1 (2014) determined that social conflict costs a large mine $20 million per week, examples of which are extensive. Schedule delays, budget overruns and, in some cases, even violence and fatalities.

Source: EY top mining and metals risks and opportunities in 2023.

The root cause of conflicts can be complex but a common factor in most instances is the belief that the wellbeing of communities has not increased in proportion to the profits of mining companies. This discrepancy is owned in no small part to the current operating models of mines which were developed and effective in a much simpler value chain. Add in the beckoning low carbon economy, the just transition, windfall taxes, resources nationalisation the expropriation of foreign operated mines and we can start to get a strong sense that current operating models are simply no longer viable.

The interconnection of social and technical complexities demands a new way of working but is there a way to create, capture and deliver value to all stakeholders in the mine of the future? Can we transition from business model to role model to create and share greater economic value and support more sustainable outcomes for both mining and society?

Business as usual is the process of extracting metallic, non-metallic mineral or industrial rock deposits from the earth. Once feasibility is determined, mining companies apply to the country government for a permit to develop and operate the mine to ultimately create, capture, and deliver value to customers and shareholders.

The typical mining business will base its strategy on producing the highest volumes of ore at the lowest possible production cost, essentially selling products of the mine to its customers, and paying royalties and taxes to the government. Various specialised teams supply the mine with equipment, material, and services. In some cases, partnerships arise between governments, operators, and communities. Positive partnerships yield benefits to all stakeholders. While it is governments who grant permits and operating licenses, it is the local community that grants a social license to operate. Considering this network of stakeholders, the current business model is a complex network of relationships, with many stakeholders and a high degree of risk tolerance. The value proposition lies in the differentiation of the mine and its strategy to achieve competitive advantage by creating a low-cost-position among its competitors. Revenue streams are impacted by commodity pricing and face high CAPEX and OPEX on the other side.

A positive feasibility study can take several years, followed by which, the mine owner must apply to the respective government to develop and operate the mine, then it is on to finalising investors. After these hurdles, then – and only then – can prospecting and exploration begin with a usual demand of a positive cashflow within the first few years. That is a lot of fingers in one pie, with every one of them expecting their slice, conflict is easy to assume. Benefits are agreed, from owner to operator, to government and shareholder but impacts are localised to communities.

The notion that a mining company’s impacts are protected by a complex supply chain are no longer viable.

There is an ever-present danger of losing the social license to operate, and long-term strategies of clear sustainable development are needed to bring communities along on a mine’s journey. This requires innovation of more than just product and process, it requires a new way of looking at value and the value chain. According to a PwC study, investors and stakeholders are concerned that the mining industry ‘is lagging’ when it comes to several factors that have not been a traditional focus. Younger generations find the industry unattractive and outdated, and far from a career or industry of choice. The digital revolution is changing how mines operate but these gains apply only to the traditional stakeholders and simply aren’t enough to change an already tarnished reputation.

As the first link in a multi-level value chain, mining produces raw materials that are essential for our roads, houses, appliances, computers, and mobile devices just to name a few. Considering the impact of the industry, it is fair to assume that its placed in a unique and daunting leadership position to effect sustainable development. So, why has the industry not visited new models? Why do many attempts to change enviably fail? Do mining companies still believe that the tried and tested is still true?

The green energy transition is entirely dependent on the metals that the mining industry produces. But as the world bands together to achieve net zero targets, mining’s environmentally and socially disruptive business activities have led to growing public concern. Circularity will be key in negating the effects of both extraction and consumption on the planet. Mines have become more centralised and more complex, and mine development methodologies that were once right are no longer viable.

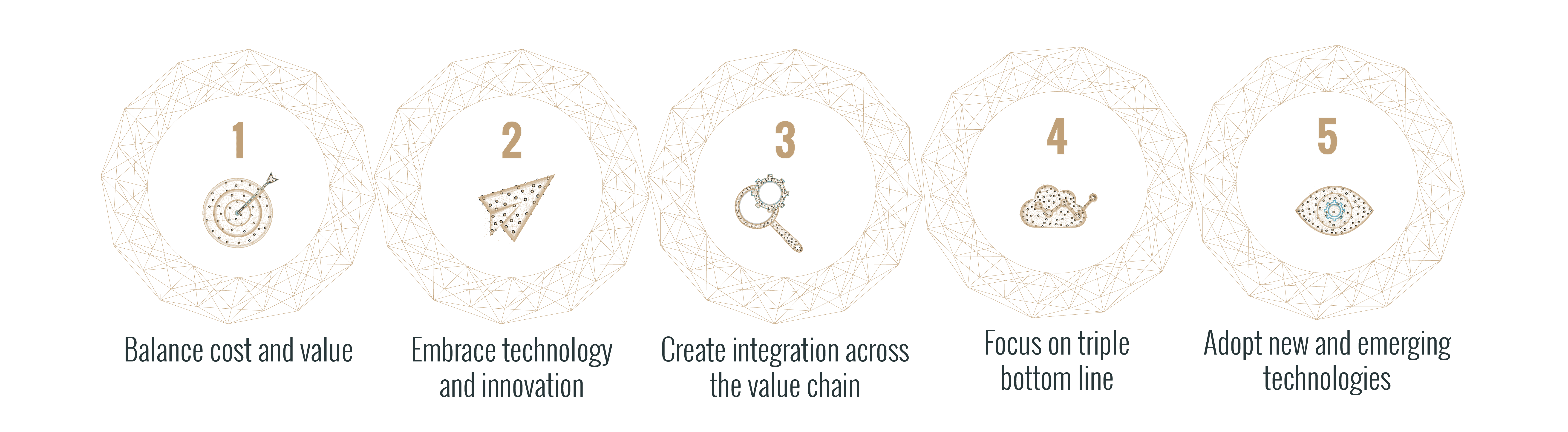

The key challenge is to produce raw materials economically and with a reduction in environmental effects and social impacts. Social license to operate and sustainable development aim to bridge the gap among the most important stakeholders involved in mining activities. Business models that prioritise sustainability are not only a lever by which to operationalise sustainability strategies but also align the respective criteria which sits within this context. These models offer the opportunities for value creation and capture through the application of circular strategies to reach the desired corporate longevity.

Circularity will be key in lessening the impacts of extraction and consumption of an industry arguably at the heart of the green energy transition. Meeting future projections for both bulk commodities and critical metals will require an integrated approach. Revolutionising workflows and structures will make it easier to protect and reconstruct ecosystems and incorporating inherent regeneration will mean that when extraction ends, the landscape is ready for the next lease holder.

Of course, pen to paper is much different to strategy to action and the current, segmented structure of mining businesses makes a positive effect for people and planet quite difficult to achieve. And redesigning these protocols and processes is much easier at greenfield operations than brownfield projects. It is not impossible but practically, how would this work?

An integrated zero waste/low carbon circular economy (CE) has spiked the interest of people across the world. Strategies and concepts are topics of debates and discussions which aim to transform processes to design products and services out of waste and pollution with enhanced economic value for supply chain networks. Can the mining industry close the production loop on systems associated with CE?

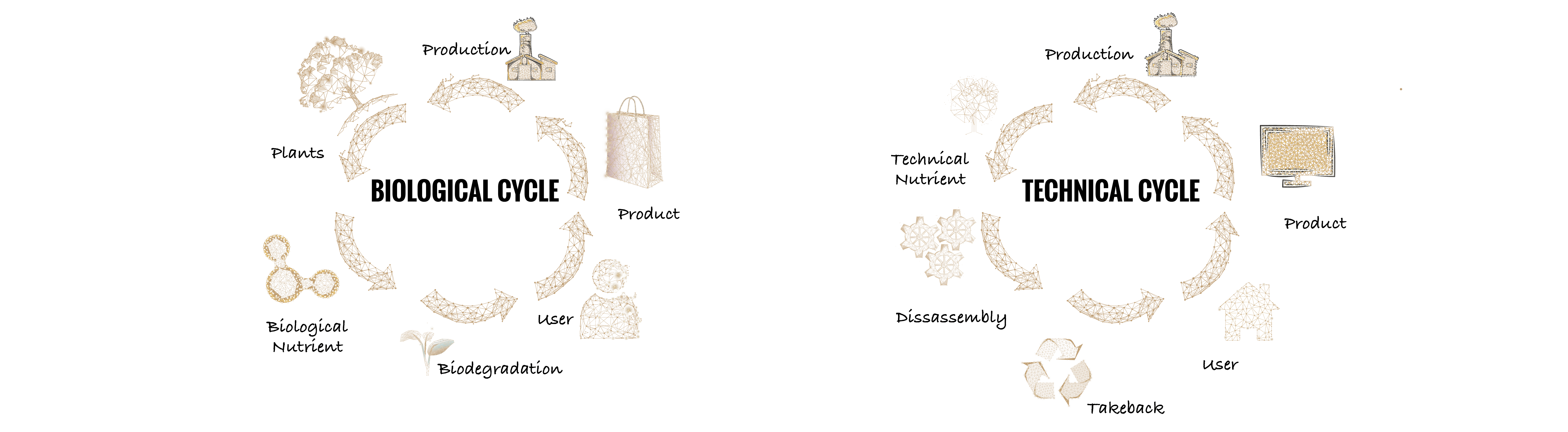

Cradle-to-cradle (C2C) is a widely used term across the industry whereby a product is designed so its materials and components can be repurposed or recycled indefinitely. This makes products “circular” and reduces their environmental impacts. C2C doesn’t eliminate the waste of old products. Instead, a product’s materials and components are repurposed or recycled. This keeps materials “in the economic loop” and saves energy during production.

Technology-driven transparency of social and environmental performance is causing some companies to see provenance of products as a potential competitive advantage.

Environmental concerns are likely to be the second biggest disruptor to the global mining industry over the next 15 years.

Reduce, reuse, recycle? In the example of titanium, around 90 percent of titanium in circulation today is recycled. But, this only satisfies 50 percent of demand. Professor Richard Herrington of London’s Natural History Museum highlighted that another factor is the time lag between a product being manufactured and it then reaching end of life; the electric vehicles being produced today probably won’t begin to be recycled until 2030. Recycling simply isn’t enough. Most CE approaches are flexible enough to be implemented, in some shape or form, during any lifecycle stage of a mine but the greatest benefits are realised when all CE strategies are considered and circularity is designed and deployed at the earliest phase of a mine’s life cycle.

Circularity on a mine site introduces ways to reduce water and energy consumption and CO2 emissions, and to eliminate waste generation. In turn, costs related to operational risk management and consumption are reduced. There have been many documented instances of environmental pollution caused by mining operations, which are often caused by leakages of mining tailings and rehabilitation costs can be substantial. Circular practices lessen the waste materials and therefore lessen the risk of potential environmental impacts. Taking action by introducing these practices also demonstrates a commitment to sustainable and responsible production. A commitment which may prove key as social expectations rise and the mining industry is increasingly tied to consumer-facing industries. The provenance of minerals could become a source of competitive advantage. If customers pay a premium for ethically sourced minerals in their technology and electric vehicles, then CE could create inviting preferential market access and responsible investment interest too. The mining industry could pave the way for a sustainable and hopeful future.

CE highlights a strong commitment to sustainable, responsible production. It aims to reduce longer term greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and environmental impacts. These strategies require innovation, new technology and capabilities which, as a result, develop diversified value chains, job creation, skills development and the restoration or regeneration of natural capital and ecosystems.

Research suggests that mining has reached peak scale and that scale reversion will be driven by changes in technology and automation as well as materials and manufacturing. Innovations have shown us how products shrink in size as their capability is improved, just look at the history of mobile phones. It is easy to assume that the mining industry is at a tipping point, economies of scale are no longer the driver of efficiency, we are moving into an era of flexibility, modularity and transparency.

With growing market and investment attention paid to the ethical and sustainable extraction of minerals and the management of these minerals throughout their lifecycle, companies who are engaged with zero waste, low carbon CE strategies will be well positioned to gain market share and maintain competitive positions.

Innovative strategies that consider a broader value chain and a deeper sense of social responsibility, whether associated with the supply of critical and strategic materials for the green energy transition, supplying materials to consumer sensitive markets like electronics or automobiles, or creating new specialty materials to develop circular products, CE strategies are efficient and effective ways to manage complex customer demands.

Circular economy leaders will look to retain conventional mining practices while innovating to keep pace with market demand and developing strategies to prepare for market disruptions that may influence future production and purchasing patterns. As with so many initiatives, the key in making mining practices more circular will lie in steady progress. Each and every change, however small, will start to add up in time.

A shift toward a more circular economy creates a substantial opportunity for mining companies that are willing to accept the challenge. By reimagining their businesses and partnering with the intermediate and end users of the essential metals and minerals they produce, these companies will lead the charge and lead the market by transforming their future footprint.

SOURCES